Dying, actively dying or terminal phase:

where death is imminent

and likely to occur within hours or days,

or, occasionally, weeks

The common signs of the active phase of dying:

• rapid and irreversible day-to-day deterioration

• restlessness and agitation

• delirium that is not related to any other underlying cause

• progressive weakness

• changed or noisy breathing

• excessive secretions in the upper airway

• peripheral shutdown and cyanosis

• decreased level of consciousness or reduced cognition

• little interest in food and fluid

• difficulty swallowing

• progressive and irreversible weight loss

• decreased urinary output that is dark in colour

• difficulty waking the resident

• reduced function in communication, mobility,

activities of daily living and social activity.

Hospice care is for any patient with a terminal illness, not just cancer patients! pic.twitter.com/C0PX9RPt7b

— Center for Hospice Care (@Center4Hospice) July 2, 2021

End-of-life care:

describes the care delivered

to people with progressive, incurable illness

to live as well as possible until they die.

It allows the supportive and palliative care needs

of both the resident and their family

to be identified and met using the palliative approach

to care for approximately the last 12 months of life.

The goals of end-of-life care are to:

• minimise distress and suffering for the dying resident, their family and carers

• provide comfort through the best pain and symptom control possible

• provide spiritual and emotional support

• provide culturally appropriate care

• provide information and support

• preserve dignity

• support choice and respect the resident’s wishes.

Comfort care measures and regular observations

should include:

• general hygiene

• mouth and eye care

• skin and pressure area care

• comfortable positioning

• micturition

• bowel care

• nutrition and hydration as tolerated

• oral nutrition and hydration as tolerated –

the benefits and risks of medically assisted

(parenteral) nutrition and hydration should be

considered before being commenced.

Address the emotional, spiritual, religious, cultural

and self-care needs of the dying resident, their

family/carer and staff.

Provide information on bereavement support for

the family/carer and staff.

that a person is imminently dying

is a crucial step

to providing high quality care".

Oxycodone is similar to morphine in its action and has a similar side effect profile. This drug is more expensive than morphine and there is no clinical evidence to support its use first line. Morphine therefore remains the drug of first choice.Seriously ill people often want to spend their last days of life at home being cared for by family or friends. This website details how carers, who are looking after a very ill person at home, can be taught to give extra (top-up) doses of medication under the skin to the person they are caring for when they experience ‘breakthrough’ symptoms (that is, symptoms not controlled by their regular medication). This will be in addition to the care they are already receiving.

http://cdhb.palliativecare.org.nz/index.htm?toc.htm?4060.htm

Oxycodone is a medicine like morphine that works as a strong pain reliever (painkiller). When used correctly at the right dose, there's no evidence that it either shortens or prolongs life. The name sounds similar to codeine, but it isn't the same.

https://www.healthinfo.org.nz/index.htm?Oxycodone-leaflet.htm

A typical initial dose of Oxycodone is 10 mg every 12 hours. Decrease the dose by 33% to 50% in special patient populations (age >65 years, hepatic impaired, or renal impaired [CrCl <60 ml/min]) and in patients taking other central nervous system depressants.

https://www.todaysgeriatricmedicine.com/archive/MA16p28.shtml

Opioids are drugs that are similar to morphine. They work for most – but not all – types of pain. Opioids have some predictable side effects that prescribers should anticipate and address:

- Constipation – laxatives should be prescribed and the dose altered until the patient's bowel movements are acceptable to them.

- Nausea and vomiting – antiemetics should be prescribed.

- Sedation – inform the patient and any family members and friends that the patient may become more drowsy or want to sleep more, so that they know what to expect.

Tips and Warnings When Starting this Opioid

Morphine (Oral)

Patients at lower doses being rotated to oral may need to start with liquid morphine sulfate (MS) in order to safely start.

Opioids come in different dose forms (oral/transdermal/transmucosal/injectable) and with different release characteristics (immediate release and modified release). Modified release (MR) preparations tend to be used to control background pain over a 24 hour period. Immediate release (IR) preparations can be prescribed and given ‘as required’ for breakthrough pain. Oral immediate release preparations act quickly, for example oral morphine will start to have an effect within 20-30 minutes with peak effect at approximately 60 minutes. Titration of the background modified release opioids is guided by how much immediate release opioids are required.

It may be necessary to convert from one opioid to another or to move from one delivery system to another when a patient’s symptoms or location change over the course of therapy.

https://palliative.stanford.edu/opioid-conversion/

Equivalency Table

https://palliative.stanford.edu/opioid-conversion/equivalency-table/

Opioid Conversion Calculator

https://www.eviq.org.au/clinical-resources/eviq-calculators/3201-opioid-conversion-calculator

Opioids Aware five headline points:

https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/services/referrals/pain/documents/gp-guidance-opioid-reduction.pdf

- Opioids are very good analgesics for acute pain and for pain at the end of life but there is little evidence that they are helpful for long term pain.

- A small proportion of people may obtain good pain relief with opioids in the long term if the dose can be kept low and especially if their use is intermittent (however it is difficult to identify these people at the point of opioid initiation).

- The risk of harm increases substantially at doses above an oral morphine equivalent of 120mg/day, but there is no increased benefit.

- If a patient is using opioids but is still in pain, the opioids are not effective and should be discontinued, even if no other treatment is available.

- Chronic pain is very complex and if patients have refractory and disabling symptoms, particularly if they are on high opioid doses, a very detailed assessment of the many emotional influences on their pain experience is essential.

Opioid toxicity

Studies have documented that morphine relieves the sensation of shortness of breath. It can relieve “air hunger” and make breathing more comfortable.

https://www.hospicesavannah.org/helping-you-understand-morphine-and-oxycodone-use/

Psychic derangements may appear when corticosteroids used, ranging from euphoria, insomnia, mood swings, personality changes, and severe depression, to frank psychotic manifestations; also, existing emotional instability or psychotic tendencies may be aggravated by corticosteroids

SSRIs approved to treat depression

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved these SSRIs to treat depression:

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/ssris/art-20044825

- Citalopram (Celexa)

- Escitalopram (Lexapro)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

PCC4U promotes the inclusion of palliative care education as an integral part of all medical, nursing, and allied health undergraduate and entry to practice training, and ongoing professional development.

http://www.pcc4u.org/

DNACPR

stands for Do Not Attempt

Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation.

It should be noted that a person or their

family cannot insist that CPR is performed.

This remains a clinical decision since

it is unethical to offer a futile treatment.

However, such cases should be handled

sensitively with evidence being presented

that makes clear the futility of CPR in the

dying person.

https://web.archive.org/web/20210619173252/http://www.st-annes.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/1.-End-Of-Life-Care-Main-Guide-v8-SINGLES.pdf

CHALLENGE:

Patient surveys indicate that most of us

– around 80% – would prefer to die at home

or our place of residence,

but in some parts of England and Wales,

fewer than 50% do

because the necessary services are not there

to support them.

Without expanding the resources

and capacity to provide palliative care

in all settings

– whether home, community, hospital, hospice or care home

– we will remain unable to meet

the choices of patients and their families.

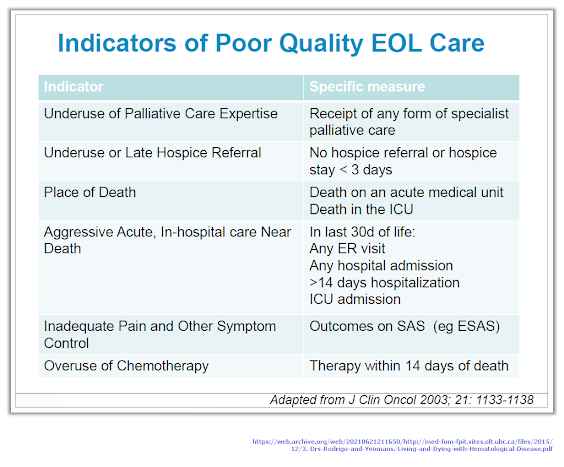

https://web.archive.org/web/20210621211650/http://med-fom-fpit.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2015/12/3.-Drs-Rodrigo-and-Yeomans.-Living-and-Dying-with-Hematological-Disease.pdf

What we mean by spirituality

existential

- If something is existential, it has to do with human existence. If you wrestle with big questions involving the meaning of life, you may be having an existential crisis.

- Existential can also relate to existence in a more concrete way. For instance, the objections of your mother-in-law may pose an existential threat to the continuation of your Friday night card game. Often the word carries at least a nodding reference to the philosophy of existentialism associated with Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Sartre, and others, which emphasizes the individual as a free agent responsible for his actions.

- Relating to or dealing with existence (especially with human existence).

Derived from experience or the experience of existence: “"formal logicians are not concerned with existential matters"- John Dewey”

Beliau bersabda,

خَيْرُ النَّاسِ مَنْ طَالَ عُمْرُهُ وَحَسُنَ عَمَلُهُ، وَشَرُّ النَّاسِ مَنْ طَالَ عُمْرُهُ وَسَاءَ عَمَلُهُ

“Sebaik-baik manusia adalah yang panjang umurnya dan baik amalannya, sedangkan sejelek-jelek manusia adalah yang panjang umurnya dan jelek amalannya.” (HR. Ahmad, at-Tirmidzi, dan al-Hakim, dari Abu Bakrah radhiyallahu ‘anhu. Hadits ini bisa dilihat di dalam Shahih al-Jami’ no. 3297)https://qonitah.com/upaya-mencari-kelapangan-rezeki-dan-perpanjangan-umur/

https://quran.com/36/65

That Day, We will seal over their mouths, and their hands will speak to Us, and their feet will testify about what they used to earn.

(Translated by Sahih International)

Ketika Tangan dan Kaki Berkata

Chrisye - Ketika Tangan dan Kaki Berkata (Taufik Ismail )

Akan datang hari

Mulut dikunci

Kata tak ada lagi

Akan tiba masa

Tak ada suara

Dari mulut kita

Berkata tangan kita

Tentang apa yang dilakukannya

Berkata kaki kita

Kemana saja dia melangkahnya

Tidak tahu kita

Bila harinya

Tanggung jawab, tiba

Rabbana

Tangan kami

Kaki kami

Mulut kami

Mata hati kami

Luruskanlah

Kukuhkanlah

Di jalan cahaya

Sempurna

Mohon karunia

Kepada kami

HambaMu

Yang hina

Common emotional responses to serious illness include:

Anger or frustration as you struggle to come to terms with your diagnosis—repeatedly asking,

“Why me?” or trying to understand if you’ve done something to deserve this.

Facing up to your own mortality and the prospect that the illness could potentially be life-ending.

Worrying about the future—how you’ll cope, how you’ll pay for treatment, what will happen to your loved ones, the pain you may face as the illness progresses, or how your life may change.

Grieving the loss of your health and old life.

Feeling powerless, hopeless, or unable to look beyond the worst-case scenario.

Regret or guilt about things you’ve done that you think may have contributed to your illness or injury.

Shame at how your condition is affecting those around you.

Denial that anything is wrong or refusing to accept the diagnosis.

A sense of isolation, feeling cut off from friends and loved ones who can’t understand what you’re going through.

A loss of self. You’re no longer you but rather your medical condition.

https://www.helpguide.org/articles/grief/coping-with-a-life-threatening-illness.htm#

Ookay kan, Bro!